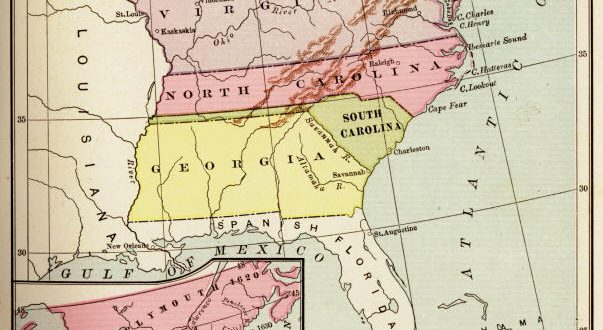

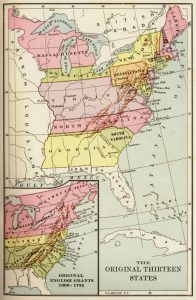

The Reason for the Thirteen Colonies

by Debra Conley

Modern textbooks conveniently omit the true reasons for the founding of the thirteen original colonies because historians trained in the rationalist tradition of academia are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with, or closed to, religiously formed history and ideas.1 How many of us learned the thirteen original colonies by name and number, but not their reason for existence? Sure, we know that Separatists founded Plymouth, Massachusetts (6th State), and that the Puritans founded Boston, but after that, our textbooks deal only with men and motives. This is an egregious and intentional omission by many, and ignorance by others. Ten of the thirteen colonies were established by religious groups for freedom to practice their beliefs, and of the remaining three New Jersey (3rd) was later re-organized and run by Quakers.

Delaware, the first state, was settled by Quakers from Pennsylvania (2nd) when that state was purchased from New York for harbor access. Georgia (4th) was granted to James Oglethorpe as a penal colony, but was one of the most receptive to religious settlers from the northern colonies. Connecticut (5th) was settled by the Puritans Thomas Hooker and John Winthrop, Jr.

Lord Baltimore was granted a charter to settle Catholics in Maryland (7th). Religious dissenters from Holland, the Netherlands, and New England moved into what became South Carolina (8th). New Hampshire (9th) was an overflow from the Puritans of Massachusetts. Virginia (10th), one of the three non-religiously founded colonies, was a joint stock venture of King James I, and eventually failed. Some think this failure was the reason King James I ordered the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh whom he had sent to secure the Jamestown colony.

The Duke of York obtained a charter to settle a colony for religious freedom seekers from Amsterdam, creating the community of New Amsterdam, later renamed New York (11th). Quakers, Baptists, and others moved south for warmer weather and more space and formed North Carolina (12th). Rhode Island (13th) was detailed in a previous column as a haven for religious independents and was the first Baptist settlement.

An interesting bit of trivia: Moravians seeking religious freedom eventually immigrated to North Carolina near Charlotte. They called this new area Wachovia after their German homeland. The name is still with us.

*Numbers indicate the order in which the colony became a state.

- Dreisbach, Daniel, Founders Famous and Forgotten (Intercollegiate Review: Fall 2007)