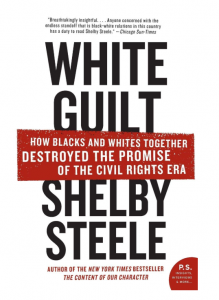

Author: Steele, Shelby

Genre:

Tags: Culture / Worldview

Series:

Rick Shrader‘s Review:

Shelby Steele wrote this book in 2006 as a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and Stanford University. Steele is now an advocate, as a black man, for conservative black values. He was a participant in the 60s push for equal rights but today sees the BLM movement as counterproductive and contrary to what the original 60s protestors advocated. By “white guilt” he means that white politicians stay in power by confessing their racism and thereby absolving themselves of it, then, white politicians stay in power because blacks have had to ask them for this confession and then expect gifts from them.

Steele describes how he discovered white guilt as a young man in the 60s when he and others pushed their college president into bending to their demands. He writes, “And this is when I first really saw white guilt in action. Now I know it to be something very specific: the vacuum of moral authority that comes from simply knowing that one’s race is associated with racism. Whites (and American institutions) must acknowledge historical racism to show themselves redeemed of it, but once they acknowledge it, they lose moral authority over everything having to do with race, equality, social justice, poverty, and so on. They step into a void of vulnerability. The authority they lose transfers to the ‘victims’ of historical racism and becomes their great power in society” (p. 24). Steele goes on, in the rest of the book, to describe how white liberals discovered how to regain the moral authority by becoming the new understanding person. He writes, “Suddenly there was a need for a ‘new man,’ or more accurately a ‘dissociated man,’ someone so conspicuously cleansed of racism, sexism, and militarism that he would be a carrier of moral authority and legitimacy” (p. 150).

I enjoyed the book because of Steele’s description of the 60s and my baby-boomer generation. I appreciated the differences he described between the valid quest for equal opportunity by the original black protests and the desire for unequal and greater opportunity by today’s protests, something his own generation never wanted.