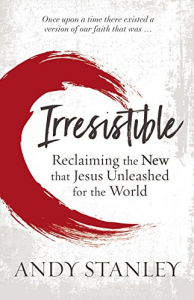

Author: Stanley, Andy

Genre: Theology - Bibliology, Theology - General

Tags: Bible, History / Story / Narrative

Series:

Rick Shrader‘s Review:

Reclaiming the New that Jesus Unleashed from the world.

Zondervan, 2018

By writing this book, Andy Stanley has taken a big step into questionable Bibliology. He has written with a positive motive: wanting to win our current generation to Christ, a generation that has either left the faith or will not come to the faith because of their distrust of the Bible. The reason for this, Stanley says, is that the Old Testament is very difficult for seekers to believe or verify, but also, that the Old Testament (he prefers “Old Covenant”) has ended and Christianity is based on the New Testament (“Covenant”). The Old Testament, then, is of little to no use for the New Testament believer.

Therefore, Stanley says on page 72 (of 322 pages), “But I hope you’ll be more than disturbed. By the time we’ve finished our journey together, I hope you’ll be ready to unhitch your faith, your theology, and your lifestyle once and for all from the old that Jesus came to replace. And I hope you will fully embrace the new Jesus came to unleash in the world, for the world.” It is difficult in a short review to retrace all of his steps in this argument, but I will try to give a fair overview of where Stanley takes the reader, give some positives and negatives, and list a few very questionable statements.

■ Stanley prefers calling the Old Testament the old “covenant.” To him, this refers to the Mosaic covenant with Israel but at times he uses the term to refer to the whole Old Testament. So by showing that the Mosaic covenant has been done away (and properly so), he ends up saying that the whole Old Testament has been done away. After quoting Rom. 7:6 that the law had been done away, he writes, “Jews were accountable to a ‘written’ code, the law of Moses. But under the new covenant, we are accountable to the Holy Spirit. Big difference” (p. 138). But then a few pages later he writes, “Bottom line, if Paul had been around in the fourth century when the bishops and theologians were brainstorming titles for the major divisions of what would eventually be called the Bible, I’m pretty sure he would have opted for the term obsolete over old. It’s not pithy, but it’s accurate” (p. 140). This becomes a major problem in following what Stanley is saying we should “unhitch.” Are we to put away the Mosaic covenant or our whole Old Testament? After all, the Mosaic covenant was only the last 1500 years of a 4000+ year Old Testament. In addition, the “law” that is done away is contained in only four of the first five books of the Bible. Should we also do away with the Psalms, Prophets, and History books? It seems he would say yes. He writes, “The designation Law and Prophets included the writings not technically considered law or prophecy. In the first century, this designation included the history and poetic literature as well. So, if you really want to follow Jesus’ example, drop the Old Testament and start referring to the first half of your Bible as the Law and the Prophets. If that seems a bit over the top, just go with the Hebrew Bible” (p. 281).

■ Along with confusion over the “old covenant,” Stanley consistently uses the “new covenant” to refer to the New Testament, all of it, and nothing else. He even quotes most of it (p. 84) from Jeremiah 31. He doesn’t approach the various views as to what and when the new covenant applies. He never discusses the future aspect of the new covenant or any prophecy related to it. To him, the new covenant is equal, across the board, to the New Testament. This gives him a neatly packaged “old covenant” and “new covenant” which he equates with the entire Old and New Testaments.

■ At times Stanley seems to be able to draw principles from the Old Testament and make good application to the New Testament believer. But for the most part he does not even feel we should make any application from the Old Testament. He writes, “If you read Paul’s epistles carefully, you’ll discover that while he considered the old covenant Scripture, he didn’t consider it binding. Just the opposite. For Paul, the Old Testament narratives provide new covenant folks with encouragement, context, and hope—but not applications to live by” (p. 202). In other places he writes, “While the Old Testament is not our go-to source for application, it is a fabulous source of inspiration. Old Testament narratives are rich in courage, valor, and sacrifice” (p. 167). “Paul never sets his application ball on an old covenant tee” (p. 168). “I too, was taught from childhood that every word in the Bible is God’s Word and, consequently, it’s all equally important and applicable” (p. 168). But Stanley does not differentiate what or how any part is “applicable.”

■ Stanley rightly points the gospel to the death, burial, and resurrection of Christ. But, he argues, since the first century believers didn’t have the “Bible,” they only evaluated moral and behavioral issues on the basis of “what does love require of me” (p. 233). He even writes, “When it comes to sexual purity, the Bible is a mixed bag with mixed messages. The New Testament isn’t. But the entire Bible, especially the Old Testament, certainly is. But even the New Testament authors don’t address consensual premarital sex directly” (p. 140). The New Testament “rule,” according to Stanley, is to ask what love requires of the person toward the other person. Ironically (I believe) this perspective of moral direction also eliminates the need of the New Testament as well as the Old. This might be, though Stanley doesn’t use the term, an example of what is today called “redemptive hermeneutics.”

■ If seekers only need to believe in the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus because the miracles of the Old Testament are hard to believe or verify, how can they believe in resurrection? I would think that would be the most difficult miracle in which to believe. An unbeliever can only believe in the resurrection because God says in His revelation that it happened. This is the same basis we believe anything about the Old Testament also, though historical things can often be partly verified by archaeology or other studies. But it seems inconsistent to say that a person can’t believe in the Old Testament events because “the Bible says,” and then accept the resurrection on the same basis.

■ I want to say that Stanley says some good things. He does not deny the inspiration of the Old or New Testaments. He is only talking about the use and application of them. He properly sees that the law of Moses was done away when the new age came. His confusion is over what the “old covenant” means. He criticized the allegorizing by many New Testament scholars in an effort to make the Old Testament law fit the New Testament. I agree, but he doesn’t deal at all with the prophecies that extend far beyond the New Testament. I take Stanley at his word that he is concerned about how people hear and receive or reject the gospel. We all should be. But it seems to me that Christians for two thousand years have believed the best way to do that is to be absolutely committed to the veracity of the whole Word of God.

■ Stanley also fails to deal with some issues that would be pertinent to his discussion. What does he do with all of the Old Testament quotations in the New Testament? One cannot read any book in the New Testament without seeing the author’s appeal to the authority of the Old Testament. Stanley never deals with prophecy in the Old or New Testaments. Not only are they quoted often in the New Testament, but these Old Testament prophecies extend beyond the New Testament. Are they also of no value to the Christian? Stanley doesn’t delineate clearly the differences among Old Testament covenants, especially the Abrahamic, the New covenant, and the Mosaic, not to mention the Davidic or the Palestinian.

■ I will add some of Stanley’s uncareful statements below. I believe they are in context though, as you will see, they surely need further explanation. However, the statements also stand on their own regardless of an explanation.

“It doesn’t help that both covenants are bound together for our convenience. The majority of people I’ve talked to who’ve abandoned their faith have lost faith in Jesus because they lost confidence in the Bible. Which part of the Bible? You guessed it—the part that doesn’t apply or include us—the Old Testament” (p. 110).

“Specifically, we don’t not commit adultery because the Ten Commandments instruct us not to commit adultery. According to Paul, Jesus followers are dead to the Ten Commandments. The Ten Commandments have no authority over you. None” (p. 136).

“Jesus treated the Hebrew Scriptures as authoritative. Paul insisted they were God-breathed. Peter believed Jewish writers were carried along by the Holy Spirit. But they never claimed their faith was based on the integrity of the documents themselves” (p. 158).

“On the other hand, there are principles, both stated and illustrated, throughout the Old Testament. Lots of sowing and reaping. Proverbs is full of common sense cause-and-effect relationships. Solomon’s financial suggestions alone are worth the price of a genuine leather-bound study Bible. But for the record, don’t do anything because Simon and Solomon say. They are not the bosses over you” (p. 166).

“But the Jerusalem Council’s decision represented something else as well. Something deeper and wider. In addition to unhitching the church from the law of Moses, their decision unhitched the church from everything associated with the law of Moses” (p. 169).

“Participants in the new covenant are not required to obey most of the commandments found in the first half of their Bibles. Participants in the new covenant are expected to obey the single command Jesus issued as part of his new covenant. Namely: As I have loved you, so you must love one another” (p. 196).

“Not surprisingly, Paul doesn’t leverage the old covenant to establish the standard for Christian morality. He leverages the believer’s inclusion in Jesus’ new covenant” (p. 204).

[Paul said], “But whatever were gains to me I now consider loss for the sake of Christ.” Stanley says, “His whatever bucket was categorized and organized around the Jewish Scriptures. Our Old Testament. Paul dismisses the primary relevance of the Scriptures he grew up with” (p. 208).

“The reason Christians should tell the truth is inexorably linked to the gospel, not a verse in the Bible. The issue isn’t that it’s written in a religious book” (p. 239).

“If we’re willing to migrate from our The Bible says-based faith and sink our roots into the fertile, blood-soaked soil of new covenant morality, much of what makes us to resistible will eventually evaporate” (p. 274-275).

“Christianity can stand on its own two new covenant, first-century feet. The Christian faith doesn’t need to be propped up by the Jewish Scriptures” (p. 278).

“Nowhere are we instructed to be prepared to defend a text or convince people to accept an authoritative book before considering the message of Jesus. Nowhere are we instructed to defend the morality of every event chronicled in the Old Testament. Just the reason for our hope” (p. 285).

“The foundation of our faith is not an inspired book. While the texts included in our New Testament play an important role in helping us understand what it means to follow Jesus, they are not the reason we follow. We don’t believe because of a book; we believe because of the event that inspired the book” (p. 294).

“Your unbelieving friends and family members don’t have to accept the Old Testament as reliable or the new Testament as inspired as a precursor to embracing Jesus as Savior. Your skeptical unbelieving friends don’t have to accept the authority of a book before accepting the historicity of the resurrection” (p. 299).

“In light of the post-Christian context in which we live, it’s time to stop appealing to the authority of a sacred book to make our case for Jesus. In the information age, that habit unnecessarily undermines the credibility of our faith. It makes our message unnecessarily resistible” (p. 303).

“’The Bible says’ establishes the Bible, as in everything in the Bible, as equally authoritative. It’s not. If it is, we have a schizophrenic faith because, as we’ve noted, the Bible contains two covenants with two different groups for whom God had two different agendas” (p. 307).

“The trustworthiness of the Bible is defensible in a controlled environment. It’s not defensible in culture where seconds count and emotions run high. So I changed my approach along with some of my terminology” (p. 314).